Exchange rate regime liquidity

In recent years, driven by a rapid expansion of the money supply or "liquidity" accompanying a sharp rise in foreign exchange reserves, China has shown signs of an emerging asset bubble, with real estate and share prices climbing rapidly. The inflation rate has also continued to rise. The Chinese government has been taking steps to tighten monetary policy in order to halt the surge in liquidity, but constrained by the exchange rate policy that seeks to achieve currency stability against the U.

China has generated a surplus in its current account - primarily in its trade balance - as well as in its capital account, which reflects the flow of funds.

These twin surpluses have exerted upward pressure on the renminbi RMB. The growth in base money has boosted broad money supply M2 by means of the credit multiplier. Consequently, China's M2 at the end of reached This growing liquidity has pushed up consumer prices as well as asset prices, namely prices of real estate and shares.

The sharp spike in real estate prices started in Shanghai and other coastal urban areas around and has now spread to inland cities. The upward trend in stock prices was triggered by the reform of non-tradable shares launched in The benchmark Shanghai Composite Index has multiplied almost six times over the past two and a half years.

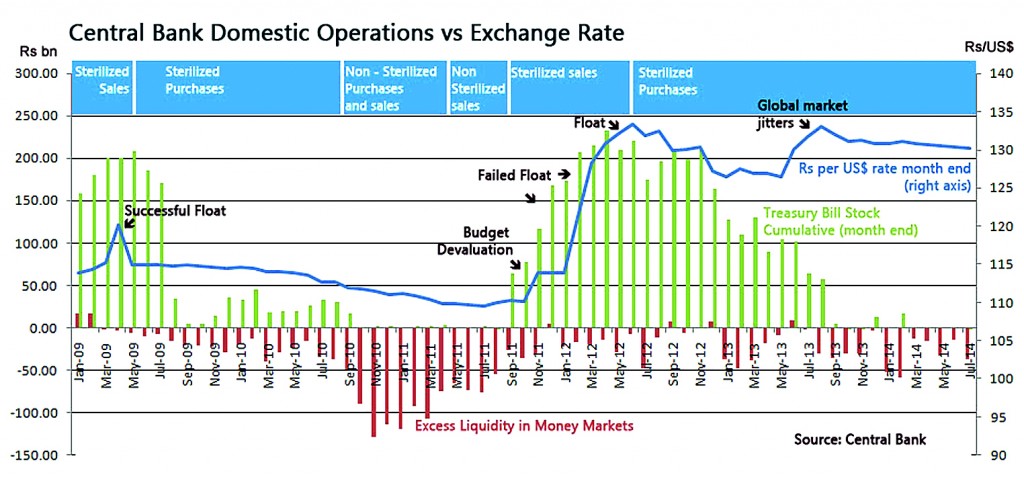

Inflation is also accelerating, with the year-on-year rate of CPI increase reaching 6. To hold down the surge in liquidity resulting from its growing external surplus, the PBOC has introduced the following three major measures, which are designed to tighten monetary policy or achieve sterilization in a broad sense.

However, the scale of intervention has become so large that sterilization operations have led to a rapid rise in interest rates, which in turn is attracting further capital inflow, making liquidity control increasingly difficult. The PBOC aims to control the credit multiplier and the money supply by raising the deposit reserve ratio that applies to banks.

It has revised this ratio upwards 11 times since , for an aggregate increase of 5. This year alone, eight revisions have been made, hiking the ratio 4. These revisions adversely affect bank profitability as the interest rates the banks can earn from the reserves deposited with PBOC are much lower than the interest rates they charge their borrowers.

The objective of interest rate hikes is to discourage demand for investment, shares, real estate, and other non-deposit financial assets by increasing borrowing costs, thereby easing the upward pressure on consumer and asset prices. Each of the foreign exchange banks has a foreign exchange allotment set for them by the State Administration of Foreign Exchange SAFE based on their size and business structure. After the designated foreign exchange banks convert foreign currency into renminbi for their customers they are required to sell the foreign currency in excess of their allotment in the interbank market.

Banks in need of foreign currency can buy the excess holdings of other banks through this interbank system. Most of the time, the supply from surplus banks exceeds the demand from banks in need of foreign currency.

This is due to the mercantilist undervaluation of the renminbi which leads to persistent external surpluses and corresponding capital inflows. To resolve the imbalance between supply and demand in the foreign exchange market, the PBoC must step in as the buyer of last resort and buy the excess currency. The chart below shows the relationship between the net foreign exchange position for the financial system and the growth in foreign reserves.

The growing divergence between the two is the result of currency appreciation. When the central bank purchases foreign exchange from banks it increases the amount of renminbi in the domestic financial system.

To prevent inflation, the PBoC takes steps to limit the effect on the money supply, through central bank bills and the required reserve ratio. To the extent that inflows are sterilized, they are taken out of circulation and not available for banks to lend out. This increase in deposits increases the denominator in the loan-to-deposit ratio, lowering the overall ratio and helping banks that are close to the regulatory limit of 75 percent. On first glance, the relatively conservative loan-to-deposit ratio of 75 percent makes it appear that banks have ample liquidity.

As a result, liquidity is often tight in the banking system. Relatively small changes in financial flows can have a large effect on the financial system. This shift, combined with reluctance by the PBoC to increase liquidity into the system, led to a dramatic spike in interbank lending rates as banks short on cash bid up the price of borrowing.