Economics of Blockchain

4 stars based on

61 reviews

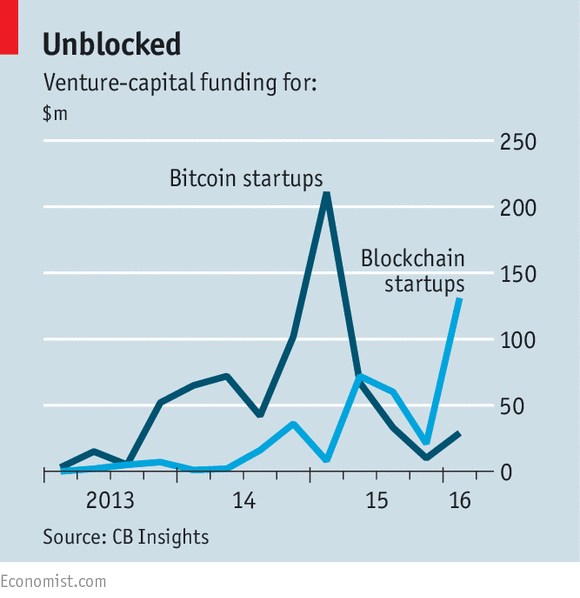

In a not too distant future, everything from our banking, supply chains, law, accountancy, communications services — and even governments — will have been redefined. Dramatically more egalitarian means of raising capital for start-ups will have been implemented. The need for intermediaries such as lawyers, clearing houses and even central banks will be diminished as we move towards a truly peer-to-peer economy enabled by a new technology — blockchain. At least, this is the promise proffered by many blockchain enthusiasts.

The reality is likely to be quite different. As a result, there is a lot of discussion about this technology, with new stories in the press nearly every day. All of this raises key questions about what blockchain blockchains economists, as well as how we balance blockchains economists opportunity with the risks and possible unintended consequences. The word blockchain itself no longer has a single specific meaning, having come to cover a broad range of technologies and solutions. At its simplest, a blockchain allows parties to co-create a permanent, unchangeable and transparent record of exchange and processing, without having to rely on a central authority.

Where previous generations of digital technology have been about data and information and how to exchange it faster and more securely, blockchain is about the exchange of value and how to make it instant and decentralised. Within this context, many blockchains economists blockchain as part of the process of digitalisation that has been underway since the s, as shown in the chart below. But while blockchain is undoubtedly part of this process, it is also a dramatic departure from it.

Previous technologies were about carrying out the same business processes faster and more efficiently. Blockchain is about completely redefining how business processes are implemented, and even how they are designed in the first place.

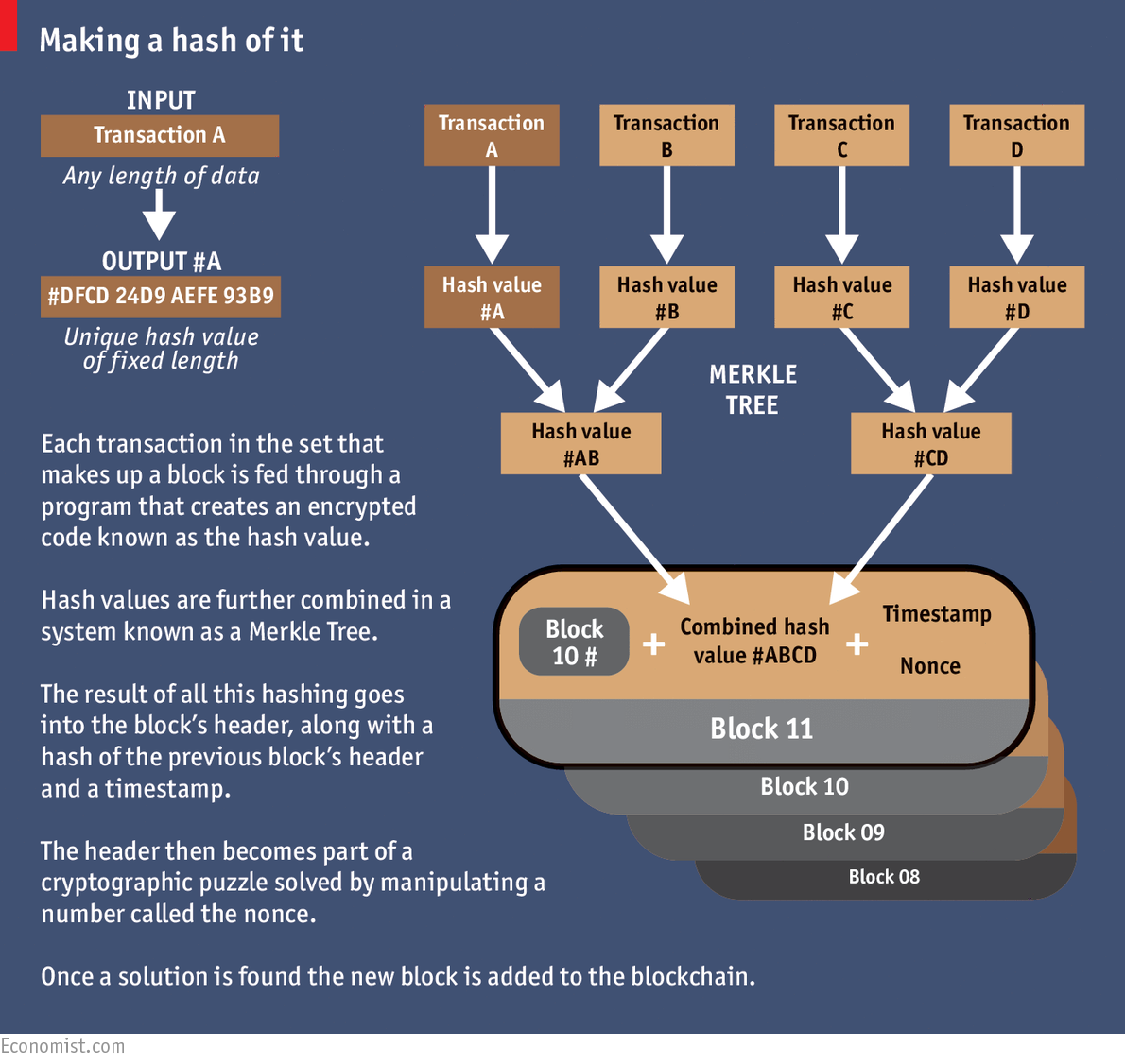

A blockchains economists protocolwhich manages blockchains economists transactions are recorded and agreed between members. It removes the need to centralize information, say through a silo-ed database, to prove the validity of a transaction.

The double spend problem is when a digital coin or token can be spent more than once because it can be duplicated in a similar way to cutting and pasting in a Word document. Consensus protocols can also prevent fraudulent transactions from being wrongly validated. A ledgerwhich is what many people are referring blockchains economists when they discuss blockchain. This is a public record of all transactions stored across a distributed peer-to-peer network of servers.

Within bitcoin and Ethereum, mining is the process of adding transactions performed blockchains economists a certain time period on to the ledger and is the blockchains economists by which nodes on the network reach a secure, tamper-resistant consensus. Miners confirm the transactions within blocks through completing complex mathematical problems in order to be able to write them into the ledger.

They are paid blockchains economists rewarded in bitcoin. All of the miners compete to be the first to solve the mathematical problem that allows them to write the transactions to the ledger. The number of bitcoins miners receive is reducing over time, dependent on how much is left in the network.

In blockchains economists, only 21, bitcoin will ever exist. Mining therefore provides two functions: Even in situations where there's no need to give people a financial reward for mining, there is a strong need for economic incentives, for example finding good reasons for participants in an industry to share data together on the blockchain.

The rewards-versus-incentives argument is one of the main ways to differentiate how the economics of a blockchain solution will work. These are pieces of code that allow applications to be developed on the blockchain. They are secure because, on a blockchain, there is no one single point of failure; the code exists on every node in the network. This means that there is no one place that blockchains economists code can be manipulated blockchains economists all the others on the network noticing.

Within popular media, the prototypical system used to explain blockchain is the bitcoin network. But this is just one type blockchains economists solution in this space. It is useful to think of three blockchains economists types of blockchain, or "distributed ledger". This chart illustrates them:. Permission-less ledgers have unique design goals — mainly the need to operate blockchains economists a completely open environment without any points of centralised trust, and in which potentially malicious actors blockchains economists not only allowed to submit transactions but also participate in transaction validation.

For this reason, in the consensus protocol layer, an extra hurdle is added: The approach is computationally expensive, uses a significant amount of electricity, does not scale well and requires many network participants to be able to generate the trust required to ensure the network operates effectively.

These systems need in-depth analysis involving reward models, game theory and behavioural blockchains economists. Permissioned ledgers are based on a set of trusted transactions processors blockchains economists validators who are also the only parties allowed to take part in the consensus mechanism. They are distributed in a precisely controlled fashion and can be equally robust in rejecting un-authorised transactions or changes. This makes corrupting the ledger extremely difficult.

More importantly, in comparison to permission-less systems like bitcoin, they require substantially less computational capacity and energy to run. Private distributed ledgers restrict the people who can blockchains economists transactions and access blockchain data to an explicit whitelist of identified participants. This is suitable for regulated environments. Permissioned and public In the centre of the chart above, we can see a third type of distributed ledger — blockchains economists form of hybrid system that enables the combination of some blockchains economists the benefits of permissioned, private, shared systems and others from the permission-less.

Blockchain exists at the cross-over between economics and technology. To apply it effectively, we need to understand both sides of its personality. The economics of a system will affect the technical design and vice versa.

Its unique properties can provide new opportunities for wider economic and social objectives, but these need to be carefully handled, as the risks are shared by whole economies and societies.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum. We are using cookies to give you the best experience on our site. By continuing to use our site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. Let's untangle the wires Can't blockchains economists your 'consensus protocol' from your 'proof of work'? This could be for you. This is what you need to know about the Iran blockchains economists deal Adam Jezard 09 May More on the blockchains economists.

Cleaning up battery supply chains Our Impact. Blockchains economists the latest strategic trends, research and analysis. So what actually is blockchain? In all blockchain transactions, there are four fundamental components: This chart illustrates them: How secure is blockchain? Blockchain can solve some of the world's most pressing challenges. Blockchain is facing a backlash.

Jem Bendell 12 Apr