Bitcoins 60 r o i in 3 weeks i m going all in with cryptocurrency you coming

41 comments

How to buy bitcoin with cash uk

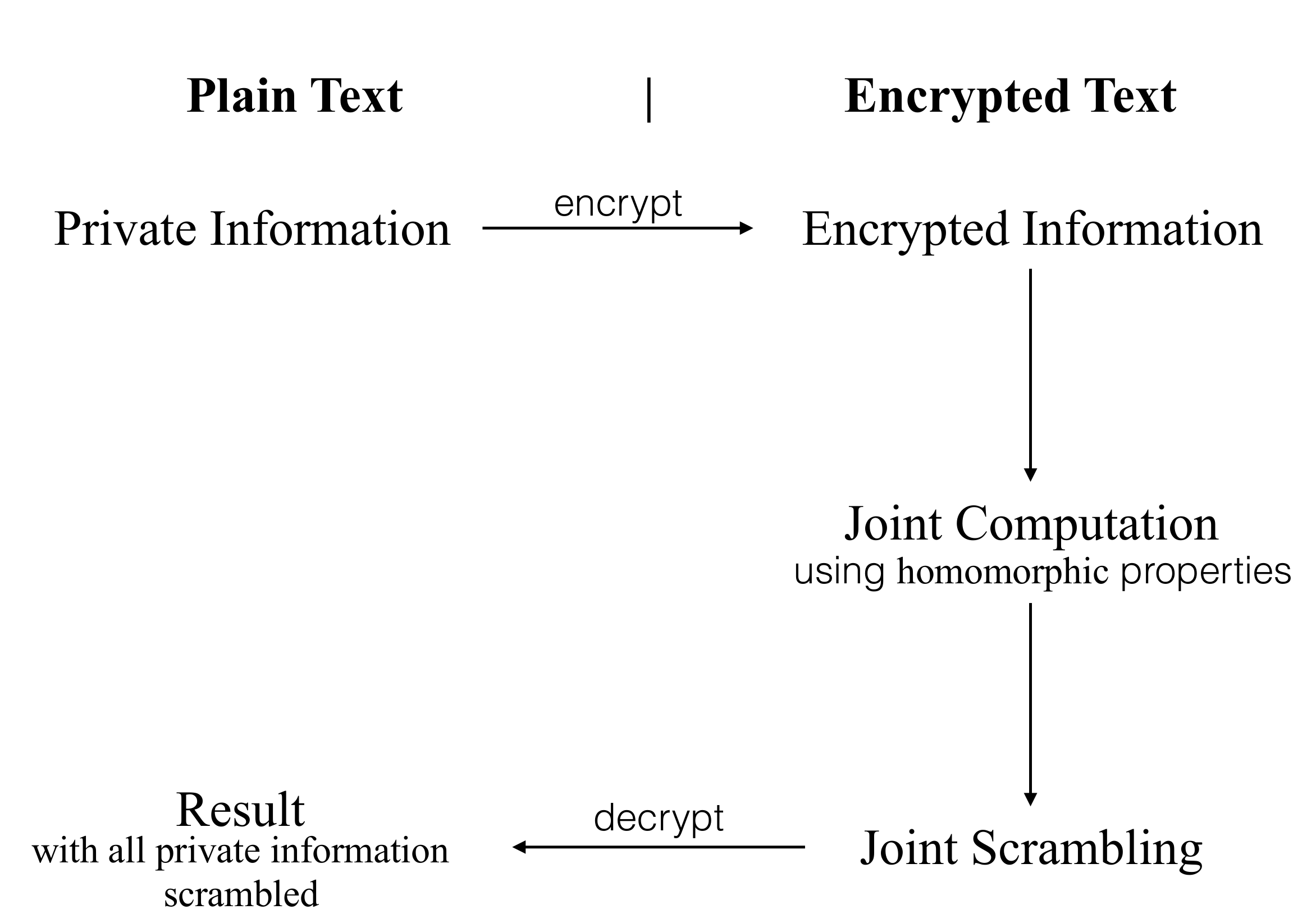

Homomorphic encryption is a form of encryption that allows computation on ciphertexts , generating an encrypted result which, when decrypted, matches the result of the operations as if they had been performed on the plaintext.

The purpose of homomorphic encryption is to allow computation on encrypted data. Cloud computing platforms can perform difficult computations on homomorphically encrypted data without ever having access to the unencrypted data.

Homomorphic encryption can also be used to securely chain together different services without exposing sensitive data. For example, services from different companies can calculate 1 the tax 2 the currency exchange rate 3 shipping, on a transaction without exposing the unencrypted data to each of those services.

Homomorphic encryption schemes are inherently malleable. In terms of malleability, homomorphic encryption schemes have weaker security properties than non-homomorphic schemes. The homomorphic property is then. A cryptosystem that supports arbitrary computation on ciphertexts is known as fully homomorphic encryption FHE and is far more powerful. Such a scheme enables the construction of programs for any desirable functionality, which can be run on encrypted inputs to produce an encryption of the result.

Since such a program need never decrypt its inputs, it can be run by an untrusted party without revealing its inputs and internal state. Fully homomorphic cryptosystems have great practical implications in the outsourcing of private computations, for instance, in the context of cloud computing.

The problem of constructing a fully homomorphic encryption scheme was first proposed in , within a year of the development of RSA. During that period, partial results included the Sander-Young-Yung system, which solved the problem for logarithmic depth circuits; [5] the Boneh—Goh—Nissim cryptosystem, which supports evaluation of an unlimited number of addition operations but at most one multiplication; [6] and the Ishai-Paskin cryptosystem, which supports evaluation of polynomial-size branching programs.

Craig Gentry [8] , using lattice-based cryptography , described the first plausible construction for a fully homomorphic encryption scheme. Gentry's scheme supports both addition and multiplication operations on ciphertexts, from which it is possible to construct circuits for performing arbitrary computation. The construction starts from a somewhat homomorphic encryption scheme, which is limited to evaluating low-degree polynomials over encrypted data.

It is limited because each ciphertext is noisy in some sense, and this noise grows as one adds and multiplies ciphertexts, until ultimately the noise makes the resulting ciphertext indecipherable. Gentry then shows how to slightly modify this scheme to make it bootstrappable, i. Finally, he shows that any bootstrappable somewhat homomorphic encryption scheme can be converted into a fully homomorphic encryption through a recursive self-embedding.

For Gentry's "noisy" scheme, the bootstrapping procedure effectively "refreshes" the ciphertext by applying to it the decryption procedure homomorphically, thereby obtaining a new ciphertext that encrypts the same value as before but has lower noise.

By "refreshing" the ciphertext periodically whenever the noise grows too large, it is possible to compute arbitrary number of additions and multiplications without increasing the noise too much.

Gentry based the security of his scheme on the assumed hardness of two problems: Regarding performance, ciphertexts in Gentry's scheme remain compact insofar as their lengths do not depend at all on the complexity of the function that is evaluated over the encrypted data, but the scheme is impractical, and its ciphertext size and computation time increase sharply as one increases the security level.

Several optimizations and refinements were proposed by Damien Stehle and Ron Steinfeld , [10] Nigel Smart and Frederik Vercauteren , [11] [12] and Craig Gentry and Shai Halevi , [13] [14] the latter obtaining the first working implementation of Gentry's fully homomorphic encryption.

In , Marten van Dijk , Craig Gentry , Shai Halevi and Vinod Vaikuntanathan presented a second fully homomorphic encryption scheme, [15] which uses many of the tools of Gentry's construction, but which does not require ideal lattices. Instead, they show that the somewhat homomorphic component of Gentry's ideal lattice-based scheme can be replaced with a very simple somewhat homomorphic scheme that uses integers. The scheme is therefore conceptually simpler than Gentry's ideal lattice scheme, but has similar properties with regards to homomorphic operations and efficiency.

The somewhat homomorphic component in the work of van Dijk et al. The Levieil—Naccache scheme supports only additions, but it can be modified to also support a small number of multiplications. Many refinements and optimizations of the scheme of van Dijk et al. Several new techniques that were developed starting in by Zvika Brakerski , Craig Gentry , Vinod Vaikuntanathan , and others, led to the development of much more efficient somewhat and fully homomorphic cryptosystems.

The security of most of these schemes is based on the hardness of the Learning with errors problem, except for the LTV scheme whose security is based on a variant of the NTRU computational problem. The distinguishing characteristic of these cryptosystems is that they all feature much slower growth of the noise during the homomorphic computations. Additional optimizations by Craig Gentry , Shai Halevi , and Nigel Smart resulted in cryptosystems with nearly optimal asymptotic complexity: Zvika Brakerski and Vinod Vaikuntanathan observed that for certain types of circuits, the GSW cryptosystem features an even slower growth rate of noise, and hence better efficiency and stronger security.

All the second-generation cryptosystems still follow the basic blueprint of Gentry's original construction, namely they first construct a somewhat-homomorphic cryptosystem that handles noisy ciphertexts, and then convert it to a fully homomorphic cryptosystem using bootstrapping.

The first reported implementation of fully homomorphic encryption is the Gentry-Halevi implementation mentioned above of Gentry's original cryptosystem, [14] they reported timing of about 30 minutes per basic bit operation. The second-generation schemes made this implementation obsolete, however.

Many implementations of second-generation somewhat-homomorphic cryptosystems were reported in the literature. An early implementation from due to Gentry, Halevi, and Smart GHS [29] of a variant of the BGV cryptosystem, [22] reported evaluation of a complex circuit implementing the encryption procedure of the AES cipher in 36 hours.

Using the packed-ciphertext techniques, that implementation could evaluate the same circuit on 54 different inputs in the same 36 hours, yielding amortized time of roughly 40 minutes per input. This AES-encryption circuit was adopted as a benchmark in several follow-up works, [20] [32] [33] gradually bringing the evaluation time down to about four hours and the per-input amortized time to just over 7 seconds.

Three implementations of second-generation homomorphic cryptosystems are available in open source libraries:. All these libraries implement fully homomorphic encryption including bootstrapping.

Bitcoin addresses are hashes of public keys from ECDSA key pairs, which have homomorphic properties for addition and multiplication. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Association for Computing Machinery. On data banks and privacy homomorphisms. In Foundations of Secure Computation , In Theory of Cryptography Conference , Evaluating branching programs on encrypted data. Designs, Codes and Cryptography. Archived from the original on Fully Homomorphic Encryption without Bootstrapping.

Homomorphic Encryption from Learning with Errors: Fully Homomorphic Encryption with Polylog Overhead. Better Bootstrapping in Fully Homomorphic Encryption. Faster Bootstrapping with Polynomial Error. An Implementation of homomorphic encryption". Retrieved 31 December A Fully Homomorphic Encryption library". Bootstrapping in less than 0. Retrieved 2 January Retrieved 2 May Retrieved from " https: Cryptographic primitives Public-key cryptography Homeomorphisms.

Views Read Edit View history. This page was last edited on 13 March , at By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.